The Astronaut and the Acid Head

August 18, 2019

First, a short warning: This

piece is about books, with only passing references to real life, (if there is

such a thing.) First, I recommend a book

by Scott Kelly: Endurance: A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery.

This memoir was a lot better than I was expecting when

I picked it off the Current Shelf at the local library. Scott Kelly spent a year on the International

Space Station. (You might have

seen the PBS documentary about it: (https://www.pbs.org/show/year-space). Meanwhile his identical twin, Mark (husband

of Gabby Gifford), also an astronaut, stayed on the good old Earth.

It’s a good mix of the gee-whiz tech stuff with the personal

insights of an intelligent and talented man.

Please don’t be put off if you’re not particularly interested in science

or space. Actually, a second-hand

recommendation might be more convincing:

Even my wife Emily, who reads 80% fiction and is not a science buff, read

it and praised it effusively.

The following paragraph from Kelly’s book may be of

interest to those who saw the movie “Gravity” directed by Alfonso

Cuarón and starring Sandra Bullock. (When

I saw the movie, I wondered if any of the ISS crew had seen it.)

“When we got the call about the [dissected] mouse last

night, we were just finishing up with movie night—‘Gravity’. We'd set up the

big screen in Node 1 facing the lab and gathered to watch it—all of us but

Samantha, [attractive Italian female astronaut] who was finishing her workout.

I've noticed a strange phenomenon when people watch movies in space: we

instinctually move to a position that looks like lying down with relation to

the screen. In weightlessness our positions make no difference in the way we feel

physically, but the association between lying down and relaxing is so strong

that I actually feel more relaxed when I get into this position. The film was

great—we were impressed by how real the ISS looked, and the five of us were an

unusually tough audience in that regard. It was a bit like watching a film of

your own house burning while you're inside it. When Sandra Bullock got out of

her space suit and floated in her underwear, Samantha happened to come floating

by the screen in her workout clothes. Later I regretted failing to get a

picture of them together.”

Scott Kelly, Endurance:

A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery, p. 122

But the part of the book I want to highlight here is

not the present-tense account of his year aboard the ISS, March 2015-March 2016,

(or attractive women floating about in their underwear), but his looking back

to the experiences that motivated him to become a fighter pilot and later an astronaut.

Kelly gave credit to one book, The Right Stuff by Tom

Wolfe, for setting him on a course that eventually led to astronaut-hood. In a later opinion piece in the New

York Times, Kelly wrote:

“In 1982, I was on my way to

flunking out of school, with no particular ambition but to party with my

friends. I was in line at the campus store one day when a book cover caught my

eye — I picked up the book while I waited in line, and by the time I reached

the cash register I was so engrossed I bought the book and took it back to my

dorm. By the next day, I had finished it and had found my life’s ambition: I

was going to fly military jets off an aircraft carrier, become a test pilot,

and maybe even become an astronaut.”

“I had known these pursuits existed before, of course,

but Tom Wolfe’s prose brought them to life in a way that spoke to me as nothing

else had before. As a terrible student with severe attention problems, I was a

poor candidate to achieve any of these goals. But I had achieved them, and I

wanted to thank Tom Wolfe, who died on Monday at the age of 88, for the part he

had played in my life by sending him a photograph of myself holding the book in

the space station.”

Kelly was a college freshman at the time. At first a series of articles Wolfe started

in 1973 for Rolling Stone magazine, The Right Stuff came out in 1979.

It set me thinking about how books influence

people. Obviously, not many people choose

a life-path because of reading one book.

But apparently, some do, at least this one man. The irony is that, by all accounts, Kelly was

not much of a reader during high school and his first year of college, but when

he did pick up a book and read it, Wham!...he was off and running. One book!

Naturally, I couldn’t help comparing myself—my young

self-- to Kelly. Unlike him, I was a

voracious reader all through high school and college. But I cannot to this day recall one book that

influenced me as much as The Right Stuff influenced Kelly.

Perhaps, by the sheer volume and breadth of my reading, I was inoculated. For example, I read Moby Dick, but had no

desire to become a whaler or even to go to sea.

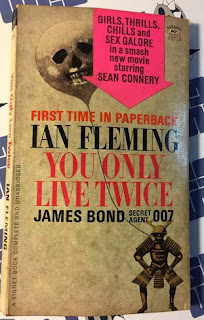

I read all of Ian Fleming’s 007 series (12 novels), but never seriously

considered a career in espionage. (The

“womanizing” part came later and of its own accord. I can’t blame Bond for that, and I admit I

never came close to his proficiency in this pursuit.)

This

was my first Fleming book.

In high school, I read both big novels by Ayn Rand [1],

but unlike Paul Ryan, was not inspired to become a conservative Republican

politician. The more I read, it seems,

the less inspired I was by any one author or book.

There were two exceptions. The first came early. I was in eighth or ninth grade when I read A

Sense of Where You Are by John

McPhee. It’s about the Princeton

basketball player Bill Bradley, who, after his college career, went on to be a

Rhodes Scholar, pro player for the New York Knicks, U.S. senator for the state

of New Jersey, and author in his own right.

His political swan song came in 2000 when he ran for the Democratic

presidential nomination. He lost to Al

Gore in the primaries. [2]

McPhee quotes Bradley, “When you have played

basketball for a while, you don’t need to look at the basket when you are in

close like this,” he said, throwing it over his shoulder again and right

through the hoop. “You develop a sense of where you are.”

|

| First paperback edition |

Back in 1965, at about the same time McPhee’s book

came out, Princeton made it to college basketball’s NCAA Final Four. That year it was in Portland, and my dad (God

rest his soul), got tickets and took me.

Princeton lost to Michigan in the semifinals, despite 29 points from

Bradley. Next night, in the consolation

game against Wichita St., Bradley scored 58, setting a record. [3]

To this day, 54 years later, it is the single most impressive display of

individual basketball skill I have ever seen.

At the end of the game, which by current standards was meaningless

because it was only for 3rd place [4], every

one of the 15,000 spectators in Memorial Coliseum was standing and roaring, not

for either team, but for one player! It

was a basketball orgasm! The game that followed, between Michigan and UCLA for

the national title, was an anti-climax.

So, in that

green period of life, I was an aspiring baller and, like millions of

other kids, I wanted to be like Bill Bradley.

I thought I needed to grow about 5-6 more inches and be a big

forward. (I wound up at 6-3 and ½, just

tall enough for a guard, the skills for which I sadly lacked.) Long story short: I failed at high school

basketball, for reasons quite apart from lack of expected growth.

I cannot blame Bradley or McPhee for my failure at

basketball, though the standard they set was impossibly high. Bradley was a fine scholar, too, and that

part of his character I was able to emulate partially. I was a pretty good student and got a

full-tuition scholarship to the University of Washington. [5]

My subsequent academic career at that that institution, unfortunately, did not

rise to anything like Bradley’s, for reasons partially explained in the

following paragraphs.

The second exception was a book I read in the summer

of 1970, I think. (That would have been

after freshman year at the UW.) It was

an earlier book by Tom Wolfe called The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,

which came out in 1968. The book is

about the author Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes

a Great Notion), who, after “experimenting” with LSD in the early 60s,

became leader of a group of like-minded artistic types who called themselves

The Merry Pranksters. The book

chronicles not only their adventures but the rise of the LSD-and

marijuana-fueled counter-culture, especially in San Francisco.

My

copy looked very much like this.

OK, so here comes the “Acid Head” part of the

title: That was me. Reading Wolfe’s book inspired me to take

LSD. Maybe “encouraged” would be a

better word. I had dropped acid a few

times during freshman year, also mescaline and psilocybin, but not until I read

Wolfe’s in the summer of ’70 did these substances have a credible proponent [6]:

Kesey and his pals.

Of course, Wolfe and Kesey received more than their

share of criticism and opprobrium for popularizing, if not encouraging, the use

of drugs. Just recently I came across

this:

A review in The Harvard Crimson identified

the effects of the book, but did so without offering praise.[9][10]

The review, written by Jay Cantor, who went on to literary prominence himself,

provides a more moderate description of Kesey and his Pranksters. Cantor

challenges Wolfe's messiah-like depiction of Kesey, concluding that "In

the end the Christ-like robes Wolfe fashioned for Kesey are much too large. We

are left with another acid-head and a bunch of kooky kids who did a few krazy

things." Cantor explains how Kesey was offered the opportunity by a judge

to speak to the masses and curb the use of LSD. Kesey, who Wolfe idolizes for

starting the movement, is left powerless in his opportunity to alter the

movement. Cantor is also critical of Wolfe's praise for the rampant abuse of

LSD. Cantor admits the impact of Kesey in this scenario, stating that the drug

was in fact widespread by 1969, when he wrote his criticism.[9][10]

He questions the glorification of such drug use however, challenging the

ethical attributes of reliance on such a drug, and further asserts that

"LSD is no respecter of persons, of individuality".[9][10]

[Wikipedia]

I carried on

dropping acid, and its psychedelic relatives, all through college and for some

years afterwards. I was never motivated

by its liberal/spiritual trappings, or because I thought it was a righteous

thing to do. Moreover, though I

respected them as authors and loved their works, I never idolized Kesey or

Wolfe.

I ate LSD because it was fun, usually in the company

of like-minded friends, male and female.

Note: I’m not bragging about how many acid trips I took (probably less

than a hundred, and that includes mescaline and psilocybin, in both natural and

processed forms.) I wouldn’t recommend

psychedelic drugs to young people. But

neither would I recommend alcohol, though beer, whiskey and vodka are

advertised 24/7 on TV and other media.

A lot of nasty, violent, stupid shit was happening in

the 60s and 70s. If I erred on the side

of non-involvement or escapism, so be it; I can forgive myself for that. Unlike Scott Kelly, I never bothered to write

Wolfe and thank him for the inspiration. [7]

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and

everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the

worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

From W. B. Yeats, “The

Second Coming.”

What else can I say?

I lacked all conviction, but I don’t boast about that, either.

I never became dependent on psychedelic drugs, but, as

the 70s dragged ever-more-depressingly on, I did become alcoholic. Booze

snuck up on me; LSD did not. (Well,

maybe the James Bond novels did have a subconscious effect. (“Vodka martini, shaken not stirred.”)) But that’s another story, connected with other

influential books.

The irony here, (if that’s the appropriate concept), is

that different books by the same author may have divergent effects on

different people. That, and the fact

that popular books when they come out are products of their times. If the Kelly twins had been born in 1950,

their lives obviously would have been much different. Given their avowed liberal leanings, I wonder

whether they’d have joined the military and fought in Vietnam. Maybe Wolfe’s earlier book, The

Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, would have influenced them as it did

me. If I’d been born in ’64, who

knows? By the time I came of age in the

80s, the counter-culture, such as it was, with all its boons and excesses, was

moribund, a thing of the past. History. Maybe

I’d have picked up a copy of The Right Stuff, become an engineer

and applied to NASA. (My eyesight wasn’t

good enough to become a fighter pilot, even if I’d wanted to.)

This piece is finished; it can’t end with

parentheses.

NOTES:

1.

1. Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead.

2. 2. “On

March 9, 2000, after failing to win any of the first 20 primaries and caucuses

in the election process, Bradley withdrew his campaign and endorsed Gore; he

ruled out the idea of running as the vice-presidential candidate and did not

answer questions about possible future runs for the presidency. He said that he

would continue to speak out regarding his brand of politics, calling for

campaign finance reform, gun control, and increased health care

insurance.” [Wikipedia]

One has to wonder what the

country—and the world—would be like if Bradley had been elected.

3. 3. Previous record was Hal Lear, Temple

U., 48 points vs. SMU, 1956.

4.

4. The so-called consolation

game was discontinued in 1981.

5.

5. Not that big of a deal. As I remember, in-state tuition at the UW in

1969-70 was less than $400 per year, considerably less than books, room and

board.

6.

6. The most celebrated proponents were

probably Tim Leary and Richard Alpert (later Baba Ram Das), but by 1969, we of

bookish bent thought them rather laughable.

7.

7. Just speculating here: I’ll bet many more people were inspired by to

take LSD by The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test than were inspired by The

Right Stuff to become fighter pilots/astronauts. Millions

more.

Interview of Wolfe by Rolling Stone:

Comments

Post a Comment