February 18, 2022

Something on the Internet recently reminded me that

this month marks the Centennial of the publication of the much-celebrated and

seldom-read novel Ulysses by James Joyce. It may have been an article in the New

Yorker: “Getting to Yes,” by Merve Emre, an Oxford scholar.[i] I read the article with an interest that was

mixed with a specific nostalgia for the times (twice) that I read Ulysses

(lo these many years ago), and a more general nostalgia for the times I

read fiction at all. It seems I don’t

read novels anymore and I wonder what happened.

The last novel I read was A Gentleman in Moscow

by Amor Towles. According to my “Read

(already been read)”[ii]

list on Goodreads, I finished it in August, 2020, a year and a half ago. I’m

fairly certain that’s the longest novel-free period of my life, at least since I

started reading fiction while in junior high school, more than 55 years ago.

I’m wondering now whether to start at that point or

work backwards from A Gentleman in Moscow. Maybe I’ll start even earlier in childhood,

when I first started reading for “pleasure.” [iii] This reading habit

started in the fourth grade, as I remember, and it was non-fiction. Our grade school[iv] had a nice little

library, and we were encouraged to browse and get books for outside

reading. We may even have earned a few

gold stars or extra credit for it if we took the trouble to fill out a brief,

rudimentary book report. At any rate, I

started reading age-appropriate books on science and natural history, things

like All about Reptiles.[v]

Also Isaac Asimov for young readers. Asimov was a polymath and incredibly prolific; one cataloguer lists over 500 titles, both fiction and non-fiction, from 1950 through 1996.[vi] I’m looking at some of his books that would have been available in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when I started reading: Here are a few that I might have read: Inside The Atom, Building Blocks of the Universe, The World of Carbon, The Clock We Live On. Though I don’t remember, I may also have read a few of his stories for kids, like David Starr, Space Ranger, or The Martian Way and Other Stories.

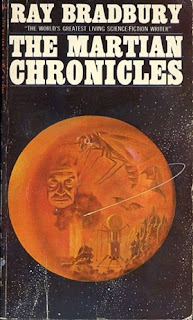

Bond started me off on the road of fiction. At about the same time, starting in 7th grade, I began reading classic horror, mostly by Poe, and science fiction, mostly by Ray Bradbury. In those days, and presumably still now, teachers would hand out in class flyers from the Scholastic Book Co. We kids would browse through the list and order cheap paperback books for 75 cents or a dollar apiece. In a week or two, the book would arrive and students like me would start reading them right away, hiding them on our laps during class.

During

high school, I read more fiction than anyone else I knew. The great books by Hemingway, Steinbeck,

Dickens. For English class, excerpts of Moby

Dick were assigned reading. I got

the book from the library and read the whole thing. The same for A Tale of Two Cities and The

Grapes of Wrath. But it wasn’t just

Great Books. Besides my second readings

of the 007 paperbacks (see above), I loved pulpy books of a fantastical bent,

especially those of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Everyone knows he wrote the Tarzan series, of which there were at least

twenty-two, published between 1912 and 1947, but fewer know of the highly

enjoyable Barsoom series, featuring the earthling hero John Carter. [xi]

Sometime during high school I read both Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand. What surprises me now, at this far remove, is how influential those books have become in American political culture, intellectual (if that is the right word) nourishment for a generation of conservatives (and neo-cons), including Paul Ryan and Allan Greenspan and Mike Pompeo. In these books, and other non-fiction screeds, Rand presented a pseudo-philosophy called Objectivism. Trump himself, a notorious non-reader, claimed to regard The Fountainhead as a kind of personal Bible: “It relates to business, beauty, life and inner emotions. That book relates to ... everything.”

Now, 55 years later, I’m trying to figure out what kept me going through the 1200 pages of Atlas Shrugged. Obviously, it wasn’t just Rand’s “philosophy,” though perhaps I found it provocative. No, it was the stories, which generated just enough narrative steam to keep me plowing through them. I do remember being a little proud of myself for getting through my first novel of over 1000 pages, a personal record. More importantly, even then I had been rendered immune, by both nature and nurture, to right-wing thinking. (I have written about it in a series of blogs called “Knee Jerk: Confessions of an Old White Liberal.”[xii])

1984

I read George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984. And I daresay that with the latter work I gained more than passing familiarity. In fact, I was cast in the Senior Play as the protagonist, Comrade Winston Smith. [xiii] For me personally, it was more an exercise in memory than a chance to develop my acting skills;[xiv] I had to memorize more than a thousand lines. Acting in a play was somewhat like being engrossed in a novel.

I read George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984. And I daresay that with the latter work I gained more than passing familiarity. In fact, I was cast in the Senior Play as the protagonist, Comrade Winston Smith. [xiii] For me personally, it was more an exercise in memory than a chance to develop my acting skills;[xiv] I had to memorize more than a thousand lines. Acting in a play was somewhat like being engrossed in a novel.

My comrades in 1984. Girl at far left was my love interest. Notice how she signed the photo: “C. J.”: Comrade Julia. Comrade O’Brien, my tormenter, played by Tom T., standing far left.

I continued reading furtively during classes, during those times

when my attention was not fully engaged in what was going on—which was

frequently. In the summertime, if I

didn’t have to get up early to work at a part-time job, I’d read far into the

night, sometimes until the birds started singing and the sky turned light. Accordingly, I’d often not get up till after

noon. Sometimes my friend C. would come

and tap on my bedroom window. “Get up,

man! We’ve got shit to do today! Looking back, I wonder how I had enough time to

remain physically active, but I did a lot, playing sports during the school

year and working (when I could) and playing golf in the summer. But I fell behind some of my friends in

learning practical skills, like, for instance, car mechanics and carpentry. Nor did go in for hunting and fishing, perhaps

healthier time-consumers.[xv]

I realize now, 50-55 years later, that in those green days

there was time enough, and energy, for everything. Any extra time was dedicated to reading

fiction.

How It Started

Back even further: Might as well use the memories I still retain, here at age 71, before I lose them entirely. I was not a particularly precocious reader. I was taught in the 1st Grade at a Catholic school in Portland called Ascension. I’m trying to dredge up the name of our 1st Grade teacher: Sr. Clemencia maybe. She was a nun, obviously, and wore the habit. We learned the alphabet and some simple phonetic rules. And before long got started on the famous Dick and Jane reading primers. [xvi]

Figure 11956 ed. It looks familiar, even 65 years later. Our class was "reading" it in '57.

I do remember that sometime during that first year the class was split into “fast” and “slow” groups, and that I was so proud to be placed into the fast one. Six years old and I was already becoming competitive at school; I wanted to be the best. I remember just as well a little girl named Sally, who was not only cute as a button but just as smart as me and probably a good deal smarter. (Looking back, I think she may already have been taught to read at home.) She was like the nun’s helper in the fast group. It was she who taught me the tricky little monosyllable “the,” which did not seem to conform to the simple phonetic guidelines we had been learning. She may have said something useful like “Some words you just have to remember,” a dictum that of course proved true. I’ll always remember Sally and realize now that I loved her.

Back even further: Might as well use the memories I still retain, here at age 71, before I lose them entirely. I was not a particularly precocious reader. I was taught in the 1st Grade at a Catholic school in Portland called Ascension. I’m trying to dredge up the name of our 1st Grade teacher: Sr. Clemencia maybe. She was a nun, obviously, and wore the habit. We learned the alphabet and some simple phonetic rules. And before long got started on the famous Dick and Jane reading primers. [xvi]

Figure 11956 ed. It looks familiar, even 65 years later. Our class was "reading" it in '57.

I do remember that sometime during that first year the class was split into “fast” and “slow” groups, and that I was so proud to be placed into the fast one. Six years old and I was already becoming competitive at school; I wanted to be the best. I remember just as well a little girl named Sally, who was not only cute as a button but just as smart as me and probably a good deal smarter. (Looking back, I think she may already have been taught to read at home.) She was like the nun’s helper in the fast group. It was she who taught me the tricky little monosyllable “the,” which did not seem to conform to the simple phonetic guidelines we had been learning. She may have said something useful like “Some words you just have to remember,” a dictum that of course proved true. I’ll always remember Sally and realize now that I loved her.

It astounds me now when I realize that just ten years later, in another school in another town in another state, I was reading Poe, Dickens, Bradbury and Steinbeck, among others. That’s how quickly kids learn, and how some pick up the reading habit, or maybe more accurately in my case, the obsession/compulsion.

In the summer of ’69, after graduating high school, I worked

on a surveying crew for the U. S. Forest Service at the Wind River Ranger

Station near Carson, Washington. My

crewmates that summer were college guys from around the U.S., and I discovered

that a few of them, like me, were novel readers as well. And so, after work and dinner, if we didn’t immediately

fall asleep in our bunks, we read. I

remember especially two books that got passed around that summer: Catch-22 by Joseph Heller and One

Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey.

When I got to college in the fall of 1969, my reading habits,

abnormal as they might have been, became something of an advantage. I recall checking into the dormitory

four-five days before classes began.

There wasn’t much else to do, so of course I read. During that little break, away from home and rather at loose ends, I finished Midnight Cowboy by James Leo Herlihy,

which I’d started at home and The End of the Road by John Barth,

which I’d been informed was required for my first English class, ENG 101 H.[xvii]

As I recall, both books were depressing—and this was before I really knew how “depressing” felt; I was only eighteen. I was alone in a big college dorm for three or four days, the first time I’d ever experienced that kind of solitude.

At the UW, I naturally gravitated toward the humanities, where

the required reading was what I might be doing even outside of class…or if I

wasn’t in school at all. And I enjoyed

the non-fiction reading in social science courses like anthropology and history. In

fact, I still keep a small collection of my college textbooks, like this one:

In the aforementioned ENG 101 class, there were two assigned

non-fiction books as well: Soul on

Ice by Eldridge Cleaver and the Autobiography of Malcolm X,

co-authored by Alex Haley. I mention

these two because they helped shaped my liberal political leanings. [xviii]

Master of Dune

Extracurricular reading in science fiction, something I’d begun in grade school—only seven or eight years previously, continued apace. Sometime during sophomore year, when living in a house with a group of guys I’d met in the dorm the year before, we read Stranger in a Strange Land by Robt. Heinlein and Dune by Frank Herbert.

Extracurricular reading in science fiction, something I’d begun in grade school—only seven or eight years previously, continued apace. Sometime during sophomore year, when living in a house with a group of guys I’d met in the dorm the year before, we read Stranger in a Strange Land by Robt. Heinlein and Dune by Frank Herbert.

As luck (or fate) would have it, in the spring of 1971 Herbert

came to the UW as a visiting professor and taught a GIS [xix] “seminar”

class called “Utopia/Dystopia.” Four of

the five guys pictured above got into the class, and as I recall there weren’t

more than eighteen or twenty students, all meeting around a large conference

table.

Herbert’s magnum opus Dune wasn’t on the reading list, presumably because, ecological epic that it was/is, it didn’t qualify as either utopian or dystopian. Everyone in that small class had already read it anyway. Two books that were included were Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (dystopian, which I’d read in high school) and Walden Two (utopian) by B. S. Skinner.[xx]

Frank (as he cordially bade us call him) selected from his own oeuvre something called The Green Brain (1966) [xxi], definitely a dystopian work. I don’t remember much about it; in fact, I just had to look it up on Goodreads.com.

A Dickens of a Time

Meanwhile, there were more required English classes to plow through, all of which required reading novels and poetry. In one undergraduate course—I forget which one—there were two Dickens novels I hadn’t encountered up to that time: Bleak House and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens’s last and unfinished book. [xxii] Dark, brooding novels, not the kind that get assigned in high school..

Meanwhile, there were more required English classes to plow through, all of which required reading novels and poetry. In one undergraduate course—I forget which one—there were two Dickens novels I hadn’t encountered up to that time: Bleak House and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens’s last and unfinished book. [xxii] Dark, brooding novels, not the kind that get assigned in high school..

It’s All Greek (and Latin) to Me

I read lots of novels, but I wasn’t an English major. Instead, I majored in Classics. [xxiii] As it happened, my high school was one of the rare public high schools that offered Latin as a foreign language. [xxiv] For whatever reason—and I am hard put to come up with a rational explanation at this far remove, I continued with Latin in my freshman year and started taking Greek as a sophomore. One reason may have been that Classics majors got to take classes in the original UW building, Denny Hall. [xxv] It was a cool building to hang out in. Classics majors had a special privilege; we got a key to the Classics Dept. Reading Room, whose large leaded windows faced out front of the building down a slope and facing east, like an eye observing the quad and upper campus. The room inside was quiet, perhaps too quiet, and when I sat down with the intention to study, always had trouble staying awake.

I read lots of novels, but I wasn’t an English major. Instead, I majored in Classics. [xxiii] As it happened, my high school was one of the rare public high schools that offered Latin as a foreign language. [xxiv] For whatever reason—and I am hard put to come up with a rational explanation at this far remove, I continued with Latin in my freshman year and started taking Greek as a sophomore. One reason may have been that Classics majors got to take classes in the original UW building, Denny Hall. [xxv] It was a cool building to hang out in. Classics majors had a special privilege; we got a key to the Classics Dept. Reading Room, whose large leaded windows faced out front of the building down a slope and facing east, like an eye observing the quad and upper campus. The room inside was quiet, perhaps too quiet, and when I sat down with the intention to study, always had trouble staying awake.

Figure 3: Denny Hall, U.W.

Besides its collection of ornate old editions lining the shelves, the Reading Room also contained an invaluable resource for students (like me) who were struggling with Latin and Greek texts. These were bilingual Loeb Series [xxvi], all of which had the original Greek or Latin on the left page and the English translation on the right. Green for Greek (easy to remember) and red for Latin.

With all that, problem was that not much extensive reading

got done. Fortunately, there were a few

classes offered of Greek and Latin works in English, in which students

including non-majors could read much more.

Again consulting my transcript, I see that in Winter Quarter 1970, as a

mere lad of 19, I took Classics 427, Greek Tragedy in English. We were able to get through the Oresteia

Trilogy[xxviii]

by Aeschylus, the Oedipus plays[xxix]

by Sophocles, and two or three plays by Euripides, including the Medea. As I remember, that was a larger class that

had some pretty smart students from outside the Classics Dept. I got a B, which was probably a gift from the

instructor. That was fifty-two years

ago, and looking back, I cannot remember anything more essential to my

education. During the same term, in

order to complete the math component of what was then called the “distribution requirement,”

I also took a course called Philosophy 120, Symbolic Logic. [xxx] I found it very difficult, and the D grade I

“earned” was the lowest of my rather spotty academic career. I mention this only to illustrate my rather

unbalanced intellectual development.

Young and callow as I was, I felt privileged to be exposed to

such learning and to able to absorb some of it.

During those four years, 1969-73, my academic motivation and performance

were often lacking, but not my appreciation.

The Russians Are Coming

About two-thirds through my rather spotty undergraduate career, my chums and I heard of a professor who taught Russian Lit. in English. Thus started our association with a teacher named Willis Konick. [xxxi] My transcript lists the first class as “RUSS 428: RUSS Novel in English.”

According to an article published about him when he retired in 2007, “Konick said teaching Dostoevski novels in the 1960s [and early ‘70s] was easy because he didn’t need to explain radicalism to students. The students also often came to class stoned — but he didn’t find that as annoying as today’s students, who often text-message during class, he added.” The “came to class stoned” bit was certainly true of my buddies and me.

About two-thirds through my rather spotty undergraduate career, my chums and I heard of a professor who taught Russian Lit. in English. Thus started our association with a teacher named Willis Konick. [xxxi] My transcript lists the first class as “RUSS 428: RUSS Novel in English.”

According to an article published about him when he retired in 2007, “Konick said teaching Dostoevski novels in the 1960s [and early ‘70s] was easy because he didn’t need to explain radicalism to students. The students also often came to class stoned — but he didn’t find that as annoying as today’s students, who often text-message during class, he added.” The “came to class stoned” bit was certainly true of my buddies and me.

Willis

was known for his engaging and theatrical teaching style. Fortunately, we were able to get into his

classes before he became even more popular in the later 70s and 80s.

What we actually read was the bulk of Dostoevsky’s oeuvre: The Possessed, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov. One of Konick’s Comp. Lit. classes, near the end of my undergrad career, was titled “Tolstoy and Lawrence,” which occasioned reading not only several of D. H. Lawrence’s novels, but of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. [xxxii]

What we actually read was the bulk of Dostoevsky’s oeuvre: The Possessed, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov. One of Konick’s Comp. Lit. classes, near the end of my undergrad career, was titled “Tolstoy and Lawrence,” which occasioned reading not only several of D. H. Lawrence’s novels, but of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. [xxxii]

|

| Konick performing in a class from what looks like the 70s. |

Those were some hefty books--a lot of reading on top of the work we tried to keep up with in our majors. The extra load pushed us to adopt some reading strategies that were probably not too healthy even in those days—and not recommended by educators who encourage young people to adopt a lifetime reading habit. We would frequently pull “all-nighters,” always fueled by strong coffee and usually aided by inexpensive little white pills which we called “bennies” or “cross-tops.” [xxxiii]

In order to get out of the house during a long night of reading, we might stroll to one of the all-night coffee shops near the UW campus. One of our favorites was the International House of Pancakes (IHOP), located around 43rd and Brooklyn NE. (Apparently it’s no longer there. [xxxiv]) There would be few other customers in the place at say 2:30 a.m., and it was possible to rent a table for the cost of a plastic carafe of coffee, which the server would refill for free.

Then we’d go to class the next day, “wired” as we’d say, and presumably prepared to answer questions and participate intelligently in discussions about whichever book we’d consumed the night before along with our bennies, coffee and cigarettes. To be honest, if we did say anything in class, it might have been semi-coherent, especially if we’d altered the bennies’ “upper” effect with weed. Back from school and jittery after such a night and day, we’d have to suffer the “crash,” which we could attenuate with more weed, beer and/or cheap wine. But the reading got done, which was the main objective. We were young; health be damned.

Even with all the reading I’d done, my college curriculum was

very poor preparation for gainful employment after graduation.[xxxv] I had no saleable skills or specialized

knowledge whatsoever. The next six years

in Seattle, which I sometimes call the My Years of Emerald Enchantment,

provided an unpredictable series of menial jobs, serial romantic liaisons, and

increasing dependence on alcohol. My

habit of reading fiction persisted withal and might even have deepened and

sustained me through that period. Somehow—and

this might be a big reason why I survived the period—I was able to adjust my

reading and drinking habits to include both.

I’d get drunk two or three times a week.

These would be my “social” hours, many of them frittered away at taverns

in the U. District or on Capitol Hill or downtown.

In my mid-twenties, these years, was when I got to the biggies that I missed when I was in college. Somehow I got to Ulysses by James Joyce, and, drunk as I often was, may have gotten more out of it than your “normal” reader because I’d had a better-than-average background in classical lit., i.e., I’d read the Odyssey—even some of it in Greek.

[i] Emre, Merve. “Getting to Yes.” The New Yorker, Feb. 14 & 21, 2022.

[ii] That’s the participle form of the verb, as in “Have already read.”

[iii] “Pleasure” may be the wrong word; that’s why I put it in quotes. “Escape” or “diversion” might be more accurate.

[iv] Washington Elementary, Eugene, Or.

[v] I don’t know if that’s a real title.

[vi][vi] A List of Isaac Asimov's Books (asimovonline.com)

[vi] In order: Casino Royale, 1953. Live and Let Die, 1954. Moonraker, 1955. Diamonds Are Forever, 1956. From Russia with Love, 1957. Doctor No, 1958. Goldfinger, 1959. For Your Eyes Only, 1960. Thunderball, 1961. The Spy Who Loved Me, 1962. On Her Majesty's Secret Service, 1962. You Only Live Twice, 1964. The Man with the Golden Gun, 1965.

Fleming died in 1964, so The Man with the Golden Gun was finished by a ghost writer and published posthumously. After Fleming’s death, the first writer to cash in on Bond’s popularity was Kingley Amis, with Colonel Sun in 1968.

[viii] That scene has stayed with me for a long, long time.

[ix] I enclosed this word in quotation marks because it’s a new one for me. It does not appear, as it should, between “metaphosphoric acid” and “metaphysic” in my clunky old Webster’s New Collegiate (9th ed, 1986), indicating a more recent origin. After a bit of quick Internet research, I found I was wrong. According to Collins’s online dictionary, it’s 400 years old as English, more than 2500 years old in Greek: 1600–10; ‹ Gk metáphrasis a paraphrasing, change of phrasing.”

[x] For cursing in the book, see, for example, Sex, Swearing and Other Transliterations in Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls | SeThink (wordpress.com) or

“Hemingway actually uses [R. L] Stevenson’s solution, too, in some places. In other passages he uses printable synonyms, such as befoul, besmirch, or muck, but by inserting words like unprintable or obscenity in their grammatically correct places (“Go and obscenity thyself”) he achieves something at once clear, elegant, and humorous.

Of course, were he writing today, Hemingway would have had no obvious reason not to simply print the unprintable. The book could have been filled with four-letter words of Saxon derivation standing in for the wealth of intricate crudeness that apparently exists in Spanish. Why not?”

[xi] Rudyard Kipling had this to say about the younger Burroughs: "My Jungle Books begat Zoos of [imitators]. But the genius of all the genii was one who wrote a series called Tarzan of the Apes. I read it, but regret I never saw it on the films, where it rages most successfully. He had 'jazzed' the motif of the Jungle Books and, I imagine, had thoroughly enjoyed himself. He was reported to have said that he wanted to find out how bad a book he could write and 'get away with', which is a legitimate ambition." (Edgar Rice Burroughs - Wikipedia.) In the same article, even after all these years, I note with some dismay that Burroughs was a stalwart advocate of eugenics.

Oddly enough, in the fall of 1969, my first roommate in the dorm at the University of Washington, a fellow named Bruce from Tacoma, was also a Burroughs aficionado.

[xii] (Blogs not currently available. Will have to repost them.) For more on Ayn Rand and her pernicious influence on American politics and society in general, see The Influence of Ayn Rand on Republican Politics (judeochristianity.org)

Column: This is what happens when you take Ayn Rand seriously | PBS NewsHour

Top 10 Reasons Ayn Rand was Dead Wrong - CBS News

Ayn Rand in Modern American Politics - The Atlantic

How Ayn Rand contributed to America's greed | Salon.com

“When I was a kid, my reading included comic books and Rand’s The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged. There wasn’t much difference between the comic books and Rand’s novels in terms of the simplicity of the heroes. What was different was that unlike Superman or Batman, Rand made selfishness heroic, and she made caring about others weakness.” --author Levin.

[xiii] 1984 has been adapted for stage several times. The version that we presented in high school was probably this

one, 1963.

[xiv] After the performance, I was told by a friend, “You were good; you acted just like yourself.” Looking back on it, I guess it was a kind of compliment; at least I wasn’t “acting” like someone else. How was Winston Smith supposed to act, anyway? He was just a normal guy, trying to survive in an abnormal world. Acting aside, we young thespians tried to make it as “realistic” as we could. This included Comrade O’Brien, the antagonist, slapping me, hard, several times, trying to get me to admit that 2 + 2 equaled 3, or 5, or whatever it was according to the party line—anything but the generally acknowledged “4”. Tom T., who portrayed O’Brien, would hold back during rehearsals, but when the play was on, he whacked me hard across the chops. On the more pleasant side, there were several kissing scenes with Comrade Julia. Now, very often in stage-staged kissing (so I was told), you don’t really kiss; you just kind of touch cheeks, concealing mouths and lips concealed from the audience. But C. J. and I really kissed, full on the mouth, at least during the dress rehearsal and performances. She was an attractive young gal, and I, for one, didn’t mind at all. It certainly made up for getting whacked across the face by Comrade O’Brien. And I’ll always be grateful that real rats were not used in the scenes where O’Brien and his thugs shoved my face down onto the rat cage. “No, no, not the rats!” I cried. “Anything but the rats!”

[xv] Probably my dad’s fault; he wasn’t much of an outdoorsman. When he wasn’t working (he was on the road five days every two weeks), he’d be at the country club playing golf and hanging out with his buddies.

[xvi] Dick and Jane - Wikipedia

[xvii] Honors English.

[xviii] See previous blog entry: “Confessions of an Old, White Liberal”: “My first English teacher, whose name I forget [note], was the archetype of tweedy white academic. Once again, I was lucky enough to be in an honors section, so it was a small class. I recall a few of the required books for that first quarter, Fall 1969. The Autobiography of Malcom X., co-written by Alex Haley, and Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver. (Malcom had already been assassinated in 1965. As a member of the Black panthers, Cleaver had actually run for president in 1968, but by the next year, charged with attempted murder, he had already fled to Algeria.) It’s safe to say that my first English professor was liberal, if not exactly radical. (Consulting my transcript, which does not provide the instructors’ names, I see that I got a B in the class.)

[xix] General and Interdisciplinary Studies.

[xx] More famous as a “behaviorist” psychologist than novelist. See, for example B.F. Skinner - Theory, Psychology & Facts - Biography.

[xxi] The Green Brain - Wikipedia

[xxii] Unfinished but published after Dickens’s death in 1870.

[xxiii] To this day, when on the infrequent occasion someone asks me what my major was in college, and I answer “Classics,” I have to explain what it means: The study of classical languages and civilizations, i.e., ancient Latin and Greek (and for real Classical scholars, Sanskrit and Hebrew as well.

[xxiv] R. A. long High School in Longview, WA. According to my cursory research this morning, it no longer offers Latin. Instead, as of the next academic year anyway, it offers American Sign Language, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish and French. If memory serves, in the late 60s when I was attending, available foreign languages were Latin, Spanish, and German. Home - R.A. Long High School (longviewschools.com).

[xxv] Denny Hall - Wikipedia; denny-hall-hra.pdf (uw.edu)

[xxvi] Loeb Classical Library | Harvard University Press

[xxvii] At the UW, Greek 203, which from my academic transcript I can see that I took in Spring Quarter of 1972. I got an A.

[xxviii] Oresteia - Wikipedia

[xxix] Sophocles, The Oedipus Cycle: Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone: Sophocles, Fitts, Dudley, Fitzgerald, Robert: 0884885440409: Books - Amazon

[xxx] Symbolic Logic Overview & Examples | What is Symbolic Logic? - Video & Lesson Transcript | Study.com

[xxxi] I maintained a very sporadic relationship with Willis, in later years by e-mail, until his death in 2016. Read his obituary at Willis Konick dies at 86, beloved UW professor | The Seattle Times. For an article written upon his retirement, see Beloved professor retires after 60 years at the UW | The Seattle Times.

[xxxii] But not War and Peace, which I confess I have never read—not yet, anyway.

[xxxiii] Short for benzedrine, one of the milder amphetamines. What Is Bendzedrine? History, Uses, Side Effects, and More (healthline.com)

[xxxiv] Safeco expansion to eat up U-District IHOP | News | dailyuw.com

[xxxv] June, 1973.

Comments

Post a Comment